I don't often mention members of my family in this blog, partly for reasons of taste, decency, privacy etc and partly because none of them are famous. (A forgivable oversight on their part, but an unfortunate one, given that Celebrity Begets Celebrity.) But here is a tiny glimpse into the mindset of my Life Partner: he is a complete Scrooge. He was too miserable even to wear his black "Bah Humbug!" hat this year, and his current catchphrase is "Christmas is Over!" This means that no one is allowed to play the "Christmas at King's College Cambridge" CD and we have to listen to Steve Earle instead. Festiveness is a scant resource in our house.

Anyway. The point of this post is to say It is So Not. As in, over. I really love this hidden time, between the last mince pie and the social embarrassment of not knowing who to kiss at midnight on New Year's eve. All year long, I wish there were twenty five hours in a day or eight days in a week, and now, as the year staggers to a close, there are five unlabelled days to write in. It's a shame that some of this valuable time will have to be spent marking, but there you go. At least there are no presents to buy/wrap/deliver, the hangovers have receded and the obligation to turn in to a born-again gym bunny is yet to come.

In a way, Midmas is a good time to get into training for the really important resolution, the only resolution that counts, which is to Write More. I will be Writing More in the New Year, and no matter what the distractions - surviving my PhD viva/being published/not being published/torpid teenagers/everything else you can think of - I will also be trying to focus on Process.

My great discovery as a writer has been that starting with the end in mind is not desirable. It is far better to start with the middle in mind, and stay there. The happiest place for me is the Zone, where writing happens, and nothing else matters. See you there in 2013, I hope!

Do you fancy being a writer? Want to get a book deal? Planning that Booker speech? Be careful what you wish for....

Friday, 28 December 2012

Monday, 17 December 2012

The Next Big Thing

Have been absurdly busy recently, not in a good way, more like a hamster which has accidentally nibbled some speed before jumping into its wheel. So I have been a tad hopeless about being part of a wonderful project called The Next Big Thing, which brings together writers to answer questions about their books. I was invited to take part by my lovely writer friend Susanna Jones.

Susanna is a brilliant author and her most recent novel 'When Nights Were Cold' is the gripping and atmospheric story of a group of women mountaineers in the early 20th century. Her writing is taut and spare, and full of tension. Susanna's work has already won a number of awards, including the CWA John Creasey Dagger, the Betty Trask Award and the John Llewellyn Rhys Prize, and her novels have been translated into more than twenty languages. You can find out about Susanna and her work here.

Any road. This is my response to the Next Big Thing questions - and do watch this space for news about four fellow writers and their new books.

1. What is the working title of your next book?

It has two titles: 'Dark Aemilia' and . I'm a bit of a title junkie.

2. Where did the idea come from for the book?

I was writing a historical novel for my MA at Brunel University, and it was actually meant to b be about Lady Macbeth. I had the vague idea that either she or Macbeth himself might be the Fourth Witch, so that was the title of that book. Then I started researching Shakespeare's play-world in sixteenth century London, and then I came across a necromancer called Simon Forman who wrote the first known review of Macbeth, and through him I found out about a woman called Aemilia Bassano (later Lanier).

It was basically love at first sight with Aemilia. She was Jewish, illegitimate and orphaned at 17, when she became the Lord Chamberlain's mistress. When she got pregnant he married her off to her feckless, recorder-playing cousin - but she still ended up being one of the first women in England to be a published poet. And she was - possibly - Shakespeare's mysterious and unfaithful lover, the notorious Dark Lady. I mean, what is not to like here? All my notes about eleventh century Scotland went into the bin.

3. What genre does your book fall under?

It's historical, but not a. bodice ripping or b. National Trust.

4. What actors would you choose to play the characters in a movie rendition?

This is very easy for me. Rachel Weisz is Aemilia, and Daniel Craig is Shakespeare. I'd avoid Dames Judy or Helen for Queen Elizabeth, and would go for something more unusual. Maybe Rupert Everett or Gary Oldman. Kathy Burke IS Moll Cutpurse. (Please pass this on if you happen to see any of these people.)

5. What is the one-sentence synopsis of your book?

Lady Macbeth stalks the streets of sixteenth-century London, searching for the story that will unleash her warped, demonic power.

6. Is your book represented by an agency?

I'm represented by Greene & Heaton.

7. How long did it take you to write the first draft of your manuscript?

Two years.

8. What other books would you compare this to within your genre?

I'm not sure about 'genre' exactly, but the historical writers I most admire are Rose Tremain and (of course) Hilary Mantel. But Angela Carter, Virginia Woolf and Jeanette Winterson have also influenced me. There is a bit of magic in the book. It's sort of realist magicalism.

9. Who or what inspired you to write this book?

Aemilia Bassano.

10. What else about this book might pique the reader’s interest?

It's women's-eye Shakespeare, the play-world from the perspective of the mistress/mother/whore.

Now... off to find those four other writers.

Susanna is a brilliant author and her most recent novel 'When Nights Were Cold' is the gripping and atmospheric story of a group of women mountaineers in the early 20th century. Her writing is taut and spare, and full of tension. Susanna's work has already won a number of awards, including the CWA John Creasey Dagger, the Betty Trask Award and the John Llewellyn Rhys Prize, and her novels have been translated into more than twenty languages. You can find out about Susanna and her work here.

Any road. This is my response to the Next Big Thing questions - and do watch this space for news about four fellow writers and their new books.

1. What is the working title of your next book?

It has two titles: 'Dark Aemilia' and . I'm a bit of a title junkie.

2. Where did the idea come from for the book?

I was writing a historical novel for my MA at Brunel University, and it was actually meant to b be about Lady Macbeth. I had the vague idea that either she or Macbeth himself might be the Fourth Witch, so that was the title of that book. Then I started researching Shakespeare's play-world in sixteenth century London, and then I came across a necromancer called Simon Forman who wrote the first known review of Macbeth, and through him I found out about a woman called Aemilia Bassano (later Lanier).

It was basically love at first sight with Aemilia. She was Jewish, illegitimate and orphaned at 17, when she became the Lord Chamberlain's mistress. When she got pregnant he married her off to her feckless, recorder-playing cousin - but she still ended up being one of the first women in England to be a published poet. And she was - possibly - Shakespeare's mysterious and unfaithful lover, the notorious Dark Lady. I mean, what is not to like here? All my notes about eleventh century Scotland went into the bin.

3. What genre does your book fall under?

It's historical, but not a. bodice ripping or b. National Trust.

4. What actors would you choose to play the characters in a movie rendition?

This is very easy for me. Rachel Weisz is Aemilia, and Daniel Craig is Shakespeare. I'd avoid Dames Judy or Helen for Queen Elizabeth, and would go for something more unusual. Maybe Rupert Everett or Gary Oldman. Kathy Burke IS Moll Cutpurse. (Please pass this on if you happen to see any of these people.)

5. What is the one-sentence synopsis of your book?

Lady Macbeth stalks the streets of sixteenth-century London, searching for the story that will unleash her warped, demonic power.

6. Is your book represented by an agency?

I'm represented by Greene & Heaton.

7. How long did it take you to write the first draft of your manuscript?

Two years.

8. What other books would you compare this to within your genre?

I'm not sure about 'genre' exactly, but the historical writers I most admire are Rose Tremain and (of course) Hilary Mantel. But Angela Carter, Virginia Woolf and Jeanette Winterson have also influenced me. There is a bit of magic in the book. It's sort of realist magicalism.

9. Who or what inspired you to write this book?

Aemilia Bassano.

10. What else about this book might pique the reader’s interest?

It's women's-eye Shakespeare, the play-world from the perspective of the mistress/mother/whore.

Now... off to find those four other writers.

Friday, 14 December 2012

'Tis the season

I am approaching Christmas with what I suppose I must call Mixed Emotions. First, I'm relieved. I have pretty much worked my butt off for the last three months, and I like the idea of rising late, drinking wine, and reading by a large festive fire. Second, I am chastened. The world probably won't end on December 21st, but from my perspective at least it has been a noticeably sad and horrible year. One that I will be glad to see the back of. And thirdly - for as all writers know, three is a powerful number - I am determined.

Yuletide may not seem like the season for determination, it's more about Bailey's Irish Cream and just one more layer of Milk Tray. Determination is a New Year thing, designed to offload sudden-onset cellulite and shot-putter arms. But I like to feel determined at inappropriate times. It takes the pressure off, vis a vis trying to relax and enjoy yourself. My determination is focused on Writing. There has to be a new book in 2013. The old book - much as I love it and always will - has had a enough airplay. It's like a spoiled and over-watched last child, and is still living at home when really it ought to be out in the world, fending for itself. 2013 is going to be The Year of the Dark Thriller. With a dash of humour. And this is my cue for a suitable photograph.

There is only one fail-safe cure for the affliction of wanting to write, and that is writing. It can cure all the attendant ills, the uncertainty, the waiting, the unworthy jealousy of other authors, the mad staring at rival writers' launch events at Waterstones in Taunton on Facebook et cetera. (Writers sometimes admit to being on Facebook too much, but they don't often say what they are feeling.)

I'm not going to put labels and links into this post, though I know I really should. I am going to light the fire and uncork the bottle. But tomorrow. Tomorrow there will be some Attitude.

Yuletide may not seem like the season for determination, it's more about Bailey's Irish Cream and just one more layer of Milk Tray. Determination is a New Year thing, designed to offload sudden-onset cellulite and shot-putter arms. But I like to feel determined at inappropriate times. It takes the pressure off, vis a vis trying to relax and enjoy yourself. My determination is focused on Writing. There has to be a new book in 2013. The old book - much as I love it and always will - has had a enough airplay. It's like a spoiled and over-watched last child, and is still living at home when really it ought to be out in the world, fending for itself. 2013 is going to be The Year of the Dark Thriller. With a dash of humour. And this is my cue for a suitable photograph.

There is only one fail-safe cure for the affliction of wanting to write, and that is writing. It can cure all the attendant ills, the uncertainty, the waiting, the unworthy jealousy of other authors, the mad staring at rival writers' launch events at Waterstones in Taunton on Facebook et cetera. (Writers sometimes admit to being on Facebook too much, but they don't often say what they are feeling.)

I'm not going to put labels and links into this post, though I know I really should. I am going to light the fire and uncork the bottle. But tomorrow. Tomorrow there will be some Attitude.

Sunday, 25 November 2012

Here's one that didn't win....

Apparently, George Orwell often mistook rejection for failure. He kept going just the same, in a state of gloomy optimism with which I am pretty familiar.

I entered this story in the Bridport micro fiction competition, and it didn't win. So...it was rejected. But that wasn't a failure on my part: I successfully wrote it, entered it, and am now posting it. In the spirit of success. Or something.

This is based on an actual theatre which was part of the Brighton Festival this year, and I really didn't go there, and there really was a Balkan band playing when I walked past, too busy to join the happy throng inside...

The song escaped over the addled roof-tops, the slates and chimneys and minarets. The curtains were cloud-drapes, moonlit and sun-dappled. Children ran among the giant legs. There were gryphons and unicorns and fluttering pennants. There was a pianola and roast chestnuts and a talking fish.

You were there, I expect, leaning over the table. Paying in florins and sixpences, counting the coins with rings on your fingers.

I entered this story in the Bridport micro fiction competition, and it didn't win. So...it was rejected. But that wasn't a failure on my part: I successfully wrote it, entered it, and am now posting it. In the spirit of success. Or something.

This is based on an actual theatre which was part of the Brighton Festival this year, and I really didn't go there, and there really was a Balkan band playing when I walked past, too busy to join the happy throng inside...

The Hurly Burly Café Theatre

I have never been to the Hurly

Burly Café Theatre. I have never seen the oompah Balkan quartet with the gypsy

in dreads from Dubrovnik. I didn’t buy black vodka from the pop-up bar, or sit

on the bleached grass on Leonard’s raincoat with the wind in my hair. No one

kissed me smoky when I scrounged a gold Soubrane. And when our lips didn’t

meet, it wasn’t the real thing.The song escaped over the addled roof-tops, the slates and chimneys and minarets. The curtains were cloud-drapes, moonlit and sun-dappled. Children ran among the giant legs. There were gryphons and unicorns and fluttering pennants. There was a pianola and roast chestnuts and a talking fish.

You were there, I expect, leaning over the table. Paying in florins and sixpences, counting the coins with rings on your fingers.

Wednesday, 21 November 2012

WRITING FOR YOUR LIFE

I'm preoccupied with death at the moment, the sudden and premature deaths of two people I knew, the fact my mother has a serious illness. I have just come back from a very beautiful funeral, which captured the everyday wonders of a supposedly 'ordinary' life.

One thing which came up over and over again was the fact that the person whose life we were celebrating loved stories - Discworld, the Narnia books, the Lord of the Rings. In recent weeks, I've felt as if my own concerns - with writing, and story telling and publishing what I write - are somehow trivial and self indulgent, as if I should Grow Up and get on with something else.

But I don't know how to do anything else. I can teach people, but what I teach is that writing is a way of finding meaning in life, if not the meaning of life. When someone dies, we sing songs, and read poems and the people who loved them tell stories about them, the memories and moments that live on. The music and poetry help us to survive, collectively, they keep the light burning.

And stories can do the same thing too. So that is why I write. Not to be published or famous or noticed. (Though every writer wants other people to be part of what they do.) But because I need to.

On the way back from the funeral, I got on a bus, weighed down with everything, the sadness and sorrow of it all. After a while, I saw the sun was out, shining through the mist of condensation that blurred the windows. We were passing the Brighton Pavilion, and I wiped the mist off the glass. I could see the pop-up skating rink they have set up for Christmas, empty chairs and tables waiting for the evening, a tiny glimpse of the ice through an open door. All in bright sunshine.

One thing which came up over and over again was the fact that the person whose life we were celebrating loved stories - Discworld, the Narnia books, the Lord of the Rings. In recent weeks, I've felt as if my own concerns - with writing, and story telling and publishing what I write - are somehow trivial and self indulgent, as if I should Grow Up and get on with something else.

But I don't know how to do anything else. I can teach people, but what I teach is that writing is a way of finding meaning in life, if not the meaning of life. When someone dies, we sing songs, and read poems and the people who loved them tell stories about them, the memories and moments that live on. The music and poetry help us to survive, collectively, they keep the light burning.

And stories can do the same thing too. So that is why I write. Not to be published or famous or noticed. (Though every writer wants other people to be part of what they do.) But because I need to.

On the way back from the funeral, I got on a bus, weighed down with everything, the sadness and sorrow of it all. After a while, I saw the sun was out, shining through the mist of condensation that blurred the windows. We were passing the Brighton Pavilion, and I wiped the mist off the glass. I could see the pop-up skating rink they have set up for Christmas, empty chairs and tables waiting for the evening, a tiny glimpse of the ice through an open door. All in bright sunshine.

Thursday, 1 November 2012

Plot number seven: Rebirth

And finally. We go to stories - and therefore plots - for things we can't find in Life. We are looking for patterns, for an explanation of some sort, a conclusion that can be drawn. We want the story to give us something back, a feeling of reassurance, the belief that while life ends, it also teaches. New beginnings emerge from bleak endings. There may or may not be rebirth in the hereafter, but there is certainly rebirth in the now. Or so the Hollywood screenwriters would have us believe.

I don't know what Christopher Booker says about this, because frankly I have looked at his book enough to feel pretty well informed about his point of view. His is the compendium approach to creativity, in which an assemblage of narratives, a great story pile, must surely offer something to those in search of narrative enlightenment.

Life is not neat or reassuring. Virginia Woolf thought sanity was a lie. Thing have happened in my life recently which don't suggest that life is a pattern of any kind. Experience tears holes in our reality, and there isn't much to mend them with. And yet. There is still the story of Pandora's box to keep the flame alive.

When Pandora opened the box, and all the bad things came out, all the evil and suffering and pain and horror, it seemed there was no hope. But Hope was exactly what there was, the tiny spirit trapped in the bottom of box who came fluttering out last of all. Ibsen said that human beings can't take all that much reality. Maybe he was being too harsh. Maybe all they need is a little bit of hope, enough to sustain the insanity of optimism which keeps us believing in the magic of story, and of being alive.

I don't know what Christopher Booker says about this, because frankly I have looked at his book enough to feel pretty well informed about his point of view. His is the compendium approach to creativity, in which an assemblage of narratives, a great story pile, must surely offer something to those in search of narrative enlightenment.

Life is not neat or reassuring. Virginia Woolf thought sanity was a lie. Thing have happened in my life recently which don't suggest that life is a pattern of any kind. Experience tears holes in our reality, and there isn't much to mend them with. And yet. There is still the story of Pandora's box to keep the flame alive.

Thursday, 23 August 2012

Make 'em wait.

There may or may not be seven basic plots, I have no idea. Christopher Booker says there are and he seems a knowledgeable sort of chap, though we may disagree about the reasons that Greenland's ice cover is melting and various other matters. (Him being a climate change sceptic and me being a non-driving near vegan and all that.)

And it's also true that there is a very great deal that I don't know about Plot, not to mention Theme, Characterisation, Pace, Dialogue and all the rest. I have written two published novels and one unpublished one (the best of the three, of course) and a number of short stories. The Unwritten far exceeds the Written, at this stage of my life.

But I do know one thing. The best writers know how to make the reader wait. Literary novelists may do this via the medium of endless description, or a general vagueness suggestive of profundity. (You may find, in the end, that you waited in vain.) Thriller writers approach this by deploying corpses and unexpected twists, with or without referencing Poe and The Gothic. Old school novelists Tell a Good Tale, in the manner of Stephen King or the mighty Mr Dickens. Anticipation is all. Delayed gratification is one of the greatest pleasures we can experience.

So is this the reason that I haven't yet revealed the mysteries of the Seventh Plot? Not really. I've been studying and on holiday:

Observe the reckless enjoyment and dedication to the moment demonstrated here as my son and I wait for a meal to arrive in Rhodes. Perhaps I am wondering how the holiday will end, what the twist will be, or what to write in my blog once I have covered The Seven Basic Plots. Who knows? I may or may not reveal this among other facets of a writer's craft in my next post. Now that's what I call a cliff-hanger.

And it's also true that there is a very great deal that I don't know about Plot, not to mention Theme, Characterisation, Pace, Dialogue and all the rest. I have written two published novels and one unpublished one (the best of the three, of course) and a number of short stories. The Unwritten far exceeds the Written, at this stage of my life.

But I do know one thing. The best writers know how to make the reader wait. Literary novelists may do this via the medium of endless description, or a general vagueness suggestive of profundity. (You may find, in the end, that you waited in vain.) Thriller writers approach this by deploying corpses and unexpected twists, with or without referencing Poe and The Gothic. Old school novelists Tell a Good Tale, in the manner of Stephen King or the mighty Mr Dickens. Anticipation is all. Delayed gratification is one of the greatest pleasures we can experience.

So is this the reason that I haven't yet revealed the mysteries of the Seventh Plot? Not really. I've been studying and on holiday:

Observe the reckless enjoyment and dedication to the moment demonstrated here as my son and I wait for a meal to arrive in Rhodes. Perhaps I am wondering how the holiday will end, what the twist will be, or what to write in my blog once I have covered The Seven Basic Plots. Who knows? I may or may not reveal this among other facets of a writer's craft in my next post. Now that's what I call a cliff-hanger.

Thursday, 2 August 2012

Plot number six: Tragedy

In a tragedy, things end badly. Christopher Booker says that, crudely put, a story will end either with the union of lovers or with death. In tragedy, death is usually violent and premature. But tragedy isn't necessarily depressing. One friend of mine prefers sad endings: happy endings make them feel excluded and inadequate.

There is no simple formula for tragedy, it takes innumerable forms and some of the other story types: such as the dark Quest - might also be tragedies. However, C. Booker cites five examples which illustrate the most simple and enduring tragic story structure. These are: the story of Icarus; 'Faust': 'Macbeth'; 'Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde' and 'Lolita'.

The basic outline is this: the hero/heroine embarks on a course of action which is dangerous or forbidden: they go over to the dark side. This works for a while, and there is a brief halcyon period. But then they realise they can't find satisfaction. The protagonist becomes more and more frustrated and unhappy. Attempts to make his/her position stronger or safer fail. The dream goes sour; they are trapped in a nightmare. Violent destruction follows.

Tragedy can be split into different sub-categories: the hero divided against himself (like Faust) or the hero as monster (like Humbert Humbert in 'Lolita'.) But in spite of the infinite variety within this story structure, there is a template which is useful when developing or planning any storyline. Essentially, a good plot is dynamic and there is a sense of movement and pace within the story; a sense of the dread inevitability of events.

This is the template:

1. Anticipation Stage. An unsatisfied or curious hero is tempted or attracted by something new.

2. Dream Stage. The hero commits himself to this course of action, and it all seems to be working.

3. Frustration Stage. Gradually, the situation unravels: he cannot find satisfaction or rest.

4. Nightmare Stage. This was a very bad idea. Everything spirals out of control; darkness beckons.

5. Destruction or Death Wish. It all comes crashing down. The hero meets a bad end.

Tragedies also tap into something fundamental in our psychology. Watch King Lear mourning the loss of Cordelia and you might feel a connection with the rest of humanity, and experience a flash of understanding about the universality of loss.

There is no simple formula for tragedy, it takes innumerable forms and some of the other story types: such as the dark Quest - might also be tragedies. However, C. Booker cites five examples which illustrate the most simple and enduring tragic story structure. These are: the story of Icarus; 'Faust': 'Macbeth'; 'Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde' and 'Lolita'.

The basic outline is this: the hero/heroine embarks on a course of action which is dangerous or forbidden: they go over to the dark side. This works for a while, and there is a brief halcyon period. But then they realise they can't find satisfaction. The protagonist becomes more and more frustrated and unhappy. Attempts to make his/her position stronger or safer fail. The dream goes sour; they are trapped in a nightmare. Violent destruction follows.

Tragedy can be split into different sub-categories: the hero divided against himself (like Faust) or the hero as monster (like Humbert Humbert in 'Lolita'.) But in spite of the infinite variety within this story structure, there is a template which is useful when developing or planning any storyline. Essentially, a good plot is dynamic and there is a sense of movement and pace within the story; a sense of the dread inevitability of events.

This is the template:

1. Anticipation Stage. An unsatisfied or curious hero is tempted or attracted by something new.

2. Dream Stage. The hero commits himself to this course of action, and it all seems to be working.

3. Frustration Stage. Gradually, the situation unravels: he cannot find satisfaction or rest.

4. Nightmare Stage. This was a very bad idea. Everything spirals out of control; darkness beckons.

5. Destruction or Death Wish. It all comes crashing down. The hero meets a bad end.

Tragedies also tap into something fundamental in our psychology. Watch King Lear mourning the loss of Cordelia and you might feel a connection with the rest of humanity, and experience a flash of understanding about the universality of loss.

Tuesday, 31 July 2012

Plot number five: Comedy

Okay, so after brief hiatus caused by PhD stuff and daylight-dodging teenagers, here is plot number five: Comedy, courtesy of Christopher Booker (who I have just discovered is a global warming sceptic as well as a former editor of Private Eye, so clearly this is a man with a sense of humour).

Comedy doesn't have to be funny, as anyone who has a. seen 'Twelfth Night' or b. listened to Radio Four's weekday comedy slot will tell you. Comedy is a genre of story, and the basic requirement here are that things turn out well. The Ancient Greeks kicked the whole thing off, and at the heart of the story was an 'agon' or conflict between two characters or groups. One side is dominated by a restrictive belief or obsession. The other represents the life force, truth and freedom. The happy ending comes about when the 'dark' character is forced to see things differently and reconciliation/celebration follow. Good, in other words,triumphs over Evil. Nice thought.

Aristotle called this 'anagnorisis' or recognition, the moment when something not understood before comes clear. This discovery is still central to comedy: eg Bridget Jones discovers that Mark Darcy is really pretty sexy and the awful jumper he was wearing at the Alconbury's Christmas party was an unwanted present.

There are various sub-genres of comedy: romantic comedy being the most obvious. A classic plot is one in which the lovers are kept apart because they are unaware of each other's identity, or even of their own identity. Lost parents or the discovery that one of the characters is a prince or princess can be part of the mix. Shakespeare reinvigorated the form, complicating and enriching the original classical template. But he followed the same pattern: from darkness to light, from disorder to order; from discord to reconciliation.

Love is a frequent theme of comedy, but the 21st century version of the form attempts to 'play it for laughs' even if this goal is sometimes missed. A classic 'type' in this genre is someone who thinks they have the world under control whose life plunges into chaos. Romance and order after chaos/union after separation still dominate eg in ' Four Weddings and a Funeral' in which Charles is united with his True Love when his unfortunate bride (Duckface) is waiting at the altar. The classic of the form in old school Hollywood terms is 'Some Like it Hot' which is full of confusion, cross-dressing and romantic mishaps.

There are huge variations within this form. The key elements are a. we see a group of people in enclosed world with some problems/disconnections; b. it all gets a lot worse; c. light is shed on the matter, truth is revealed, a happy feeling ensues.

Comedy doesn't have to be funny, as anyone who has a. seen 'Twelfth Night' or b. listened to Radio Four's weekday comedy slot will tell you. Comedy is a genre of story, and the basic requirement here are that things turn out well. The Ancient Greeks kicked the whole thing off, and at the heart of the story was an 'agon' or conflict between two characters or groups. One side is dominated by a restrictive belief or obsession. The other represents the life force, truth and freedom. The happy ending comes about when the 'dark' character is forced to see things differently and reconciliation/celebration follow. Good, in other words,triumphs over Evil. Nice thought.

Aristotle called this 'anagnorisis' or recognition, the moment when something not understood before comes clear. This discovery is still central to comedy: eg Bridget Jones discovers that Mark Darcy is really pretty sexy and the awful jumper he was wearing at the Alconbury's Christmas party was an unwanted present.

There are various sub-genres of comedy: romantic comedy being the most obvious. A classic plot is one in which the lovers are kept apart because they are unaware of each other's identity, or even of their own identity. Lost parents or the discovery that one of the characters is a prince or princess can be part of the mix. Shakespeare reinvigorated the form, complicating and enriching the original classical template. But he followed the same pattern: from darkness to light, from disorder to order; from discord to reconciliation.

Love is a frequent theme of comedy, but the 21st century version of the form attempts to 'play it for laughs' even if this goal is sometimes missed. A classic 'type' in this genre is someone who thinks they have the world under control whose life plunges into chaos. Romance and order after chaos/union after separation still dominate eg in ' Four Weddings and a Funeral' in which Charles is united with his True Love when his unfortunate bride (Duckface) is waiting at the altar. The classic of the form in old school Hollywood terms is 'Some Like it Hot' which is full of confusion, cross-dressing and romantic mishaps.

There are huge variations within this form. The key elements are a. we see a group of people in enclosed world with some problems/disconnections; b. it all gets a lot worse; c. light is shed on the matter, truth is revealed, a happy feeling ensues.

Sunday, 15 July 2012

The plot thickens...

Just an aside from my Christopher Booker-based musings on plotting. The image of a plot thickening, like soup, is very useful. The best plots aren't great Heath Robinson constructions put together with mechanical ingenuity, which crank up the action with creaking, wheezing effort.

The best plots seem to arise naturally, inevitably. This applies to all kinds of writing, even thrillers. I read 'The Talented Mr Ripley' recently, and while it's a work of shimmering brilliance in almost every way, it doesn't depend on death defying plot twists or mind-blowing tricks in the final act. It just sustains the tension remorselessly via the medium of Ripley's weird and warped character, and the reader's collusion with him. (There is no way we want him to be caught, even though we know everything he's done - nothing is held back.)

A great plot is not a machine. It is an organic, vegetable thing, growing inside and outside the story, the characters and the the theme. I find it useful - as I approach my fourth novel - to think about these things under separate headings, but in fact the writing process retains its messiness no matter how much time you spend trying to analyse it and tidy it all up.

Next up - the comic plot, which comes in various forms, not all of them funny.

The best plots seem to arise naturally, inevitably. This applies to all kinds of writing, even thrillers. I read 'The Talented Mr Ripley' recently, and while it's a work of shimmering brilliance in almost every way, it doesn't depend on death defying plot twists or mind-blowing tricks in the final act. It just sustains the tension remorselessly via the medium of Ripley's weird and warped character, and the reader's collusion with him. (There is no way we want him to be caught, even though we know everything he's done - nothing is held back.)

Next up - the comic plot, which comes in various forms, not all of them funny.

Friday, 6 July 2012

Plot no 4: Voyage and Return

At first sight this looks a bit like Quest with a return ticket. But the Voyage and Return protagonist isn't looking for anything specific. They are on a journey of exploration, going to a new world which is strange, unfamiliar, abnormal. At first this is astonishing and exciting, but eventually they realise they are trapped in this place, far from home, and they yearn for its familiarity and safety.

Two classics of the Voyage and Return form are Alice in Wonderland/Through the Looking Glass and The Lion the Witch and the Wardrobe. Both have examples of the 'portal' which is common to many of these stories - the route to the other world. Rabbit hole, mirror, wardrobe - they mark the end of this world and the beginning of the next. In The Wizard of Oz, the tornado is the portal, blowing Dorothy's house over the rainbow. Once the portal has done its work 'we're not in Kansas any more'. Anything can happen - reality as we know it has been left behind.

There are ancient versions of this plot, and it was also used by Defoe and Swift in Robinson Crusoe and Gulliver's Travels. Travellers' tales were widely used in popular chapbooks before the novel came into being - the wonder of another world has a deep, atavistic hold on our imagination. As does the idea of home, a place you appreciate so much more when it is far away.

But the stories don't have to be fantastical - the protagonist can enter another world in social or geographical terms, as Paul Pennyfeather does in Decline and Fall, or Harry Lime does in The Third Man.

The hero or heroine of such tales can be dreamy and unfocused or naive and open to experience. They can be generic - an adventurer, up for anything. But they do need to begin with a set of assumptions that shape their world, and in the course of the story these assumptions do have to be challenged or undermined in some way. A brilliant example of the form is another Greene novel, Travels with my Aunt, in which the narrator returns home in a way which is unexpected but satisfying. (I won't say how in case you haven't read it yet, and it's a brilliant story, clever, vivid and a real page-turner.)

At some point the new world becomes more dangerous and sinister that it is exotic and exciting. A crisis of some kind will take place, and the narrator will be in peril. Mr McGregor might be chasing Peter Rabbit to put him in a pie; the Red Queen might be threatening Alice with decapitation. Essentially, at this point they change, they expand their knowledge and awareness. Innocence is lost. The Voyage and Return plot is a plot of self discovery and 'coming of age'.

Christopher Booker (our plot guru) sums up the stages like this: 1. Anticipation Stage and 'fall' into the other world; 2. Initial fascination or 'dream' stage; 3. Frustration stage; 4. Nightmare stage and 5. Thrilling Escape and Return. Top tip - if you take one of the novels I've mentioned, you could break the action down under these headings. Or try it with another novel which seems to fit this story genre.

Two classics of the Voyage and Return form are Alice in Wonderland/Through the Looking Glass and The Lion the Witch and the Wardrobe. Both have examples of the 'portal' which is common to many of these stories - the route to the other world. Rabbit hole, mirror, wardrobe - they mark the end of this world and the beginning of the next. In The Wizard of Oz, the tornado is the portal, blowing Dorothy's house over the rainbow. Once the portal has done its work 'we're not in Kansas any more'. Anything can happen - reality as we know it has been left behind.

But the stories don't have to be fantastical - the protagonist can enter another world in social or geographical terms, as Paul Pennyfeather does in Decline and Fall, or Harry Lime does in The Third Man.

The hero or heroine of such tales can be dreamy and unfocused or naive and open to experience. They can be generic - an adventurer, up for anything. But they do need to begin with a set of assumptions that shape their world, and in the course of the story these assumptions do have to be challenged or undermined in some way. A brilliant example of the form is another Greene novel, Travels with my Aunt, in which the narrator returns home in a way which is unexpected but satisfying. (I won't say how in case you haven't read it yet, and it's a brilliant story, clever, vivid and a real page-turner.)

At some point the new world becomes more dangerous and sinister that it is exotic and exciting. A crisis of some kind will take place, and the narrator will be in peril. Mr McGregor might be chasing Peter Rabbit to put him in a pie; the Red Queen might be threatening Alice with decapitation. Essentially, at this point they change, they expand their knowledge and awareness. Innocence is lost. The Voyage and Return plot is a plot of self discovery and 'coming of age'.

Christopher Booker (our plot guru) sums up the stages like this: 1. Anticipation Stage and 'fall' into the other world; 2. Initial fascination or 'dream' stage; 3. Frustration stage; 4. Nightmare stage and 5. Thrilling Escape and Return. Top tip - if you take one of the novels I've mentioned, you could break the action down under these headings. Or try it with another novel which seems to fit this story genre.

Sunday, 1 July 2012

Plot no.3 - The Quest

The Quest story is well known and immediaetely recognizable. As Christopher Booker points out 'some of the most celebrated stories in the world are quests'. These include Homer's Odyssey; Virgil's Aeneid; Dante's Divine Comedy and Bunyan's Pilgrim's Progress. More recent quest stories are The Lord of the Rings, Richard Adams' Watership Down and Steven Spielberg's Raiders of the Lost Ark.

The key here is that it doesn't matter what the characters are searching for, as long as they are searching for something, and it doesn't matter where they go. Vital components include the hero (or heroine); a 'call to adventure', some companions who help and support the hero, but with whom their will be conflict and a perilous journey. On arrival, or near arrival, the hero/heroine will meet some final frustration or impediment. There will be a last test, or tests, and then the final goal will be achieved.

And you can go towards the light and frothy - as in Around the World in 80 days - or dark. As in Conrad's Heart of Darkness or its cinematic alter ego Apocalypse Now.

Sounds so incredibly easy I think I will start penning my Quest novel right now.

The key here is that it doesn't matter what the characters are searching for, as long as they are searching for something, and it doesn't matter where they go. Vital components include the hero (or heroine); a 'call to adventure', some companions who help and support the hero, but with whom their will be conflict and a perilous journey. On arrival, or near arrival, the hero/heroine will meet some final frustration or impediment. There will be a last test, or tests, and then the final goal will be achieved.

And you can go towards the light and frothy - as in Around the World in 80 days - or dark. As in Conrad's Heart of Darkness or its cinematic alter ego Apocalypse Now.

Sounds so incredibly easy I think I will start penning my Quest novel right now.

Wednesday, 27 June 2012

Plot 2 - Rags to Riches

Christopher Booker makes the point that this story also appears in the Bible - Joseph the Dreamer becomes Joseph the great leader. And the rags to riches story is associated with the fairy tale ending, which can be sugary and twee. (For my money, they should have cut the Strictly Ballroom scene at the end of Scott and Fran's dance and missed out the group dance-athon to 'Love is in the Air'. Now that's what I call cheese.)

But the feel-good factor varies - both Jane Eyre and David Copperfield are rags-to-riches stories in which the suffering far outweighs the happiness. (Jane Eyre was famously only able to marry Mr Rochester after Charlotte Bronte blinded him; she (almost certainly) killed off M. Paul in Villette. Happy endings weren't Ms Bronte's thing.) Frequently, these stories begin with the childhood of the protagonist, and show that they need to ovecome dark forces aligned against them - the Ugly Sisters in one form or another.

The classic form of this story falls into three sections - the protagonist's fortunes seem to imrpove for a while (Jane meets Mr Rochester, they fall in love and are about to marry) then there is a huge setback (he is married to Bertha Mason) and then there is a gradual return to good fortune again (Jane's equilibrium is restored when she meets her cousins, but she is drawn back to Thornfield Hall, apparently by supernatural forces or a deep instinct that Mr Rochester needs her).

Hollywood likes to run the rags to riches story as the classic Tale of the Arist, in which the artist is ignored for years and is eventually rich, famous and united with their True Love. This may be responsible for the misguided idea among some wannabe writers that this is the inevitable late stage of a writing career. If so, I am still in my Ignored period, and not expecting to be united with the Booker prize any time soon.

There is of course a dark side to the Rags to Riches story - there is a dark side to everything. The biopic which ends not with success but the artist falling victim to drugs and/or sycophants and groupies is one example. Riches aren't always what they seem - the pursuit of money and success can be an empty quest. But what we are talking about here is plot, and as a plot device the tale of the poor, obscure, plain Jane who wins the handsome prince has been told a thousand times - and will be told a thousand more times.

Monday, 25 June 2012

Beating the monster

Herewith Plot Number One. Among the oldest stories we have is Beowulf, the tale of a lone hero who fights a mighty monster in its lair. Christopher Booker points out that this ancient myth has almost exactly the same plot as the rather more recent Jaws: hero, monster, water, gore.

The earliest example of the 'overcoming the monster' story dates back even further than Beowulf: the Epic of Gilgamesh is more than 5,000 years old. The key to this plot is that the hero must challenge some embodiment of evil. It can be human, or similar to human - a witch or a giant. It can be animal or mythical beast - a wolf or a dragon. And it may threaten a community, or even the whole world. It may, as an optional extra, harbour some great treasure or a hold a 'princess' captive. And this evil has to be overthrown.

The hero must confront the monster, often with special weapons or with a borrowed magic power. Battle is joined in the lair: cave, forest, sea, or other enclosed place. A terrible fight takes place. At one point, it seems there is no way the hero can win. Then, there is a reversal of fortune and he outwits the monster and makes a thrilling escape. The monster is slain,and the hero takes the booty, or marries the damsel in distress.

'Overcoming the monster' is a Hollywood staple. The modern archetype in the modern monster myth is James Bond. What Plot Number One lacks in subtlety it makes up for in special effects, whether they are provided by CGI or a travelling minstrel telling a story in the firelight.

This plot encompasses thrillers, Westerns and war films. At it heart is constriction versus freedom; imprisonment versus liberty. Tomorrow - plot number two - Rags to Riches.

The earliest example of the 'overcoming the monster' story dates back even further than Beowulf: the Epic of Gilgamesh is more than 5,000 years old. The key to this plot is that the hero must challenge some embodiment of evil. It can be human, or similar to human - a witch or a giant. It can be animal or mythical beast - a wolf or a dragon. And it may threaten a community, or even the whole world. It may, as an optional extra, harbour some great treasure or a hold a 'princess' captive. And this evil has to be overthrown.

The hero must confront the monster, often with special weapons or with a borrowed magic power. Battle is joined in the lair: cave, forest, sea, or other enclosed place. A terrible fight takes place. At one point, it seems there is no way the hero can win. Then, there is a reversal of fortune and he outwits the monster and makes a thrilling escape. The monster is slain,and the hero takes the booty, or marries the damsel in distress.

This plot encompasses thrillers, Westerns and war films. At it heart is constriction versus freedom; imprisonment versus liberty. Tomorrow - plot number two - Rags to Riches.

Sunday, 24 June 2012

To plot - or not?

A good plot is, my agent once said to me, like wearing really good underwear. It gives structure and coherence to your work. Plots are certainly essential in some genres - thrillers and crime novels in particular. The old-school, well crafted novel is likely to be built on solid foundations. (Or an expensive set of bra and knickers.)

But literary fiction is often more reliant on language, ideas and intellectual audacity than plot. I studied for my MA at Brunel, which favours solid plot construction. At UEA, still the creative writing equivalent of Oxbridge, plot is seen as somewhat middlebrow.

When I think about books I have read, what do I remember? Atmosphere, often, and character and scenes. In Bleak House, the brilliant opening and its depiction of foggy London. In Pride and Prejudice, the character of Lizzie Bennet with her razor wit and fine eyes. In The Girls of Slender Means, Selina Redwood squeezing through the tiny attic window with the Schiaparelli dress.

But I do remember plot. Both Affinity and Fingersmith turn on audacious and ingenious plot twists, and so does The Woman in Black. Sometimes plot can sneak up and change the whole meaning of a novel - English Passengers does this superbly and made me weep. Plots can be stunningly well executed - as in The People's Act of Love, or tragically simple, as in The End of the Affair.

I also suspect that, like me, many writers are intimidated by the idea of constructing plot. It always struck me as the Maths homework of fiction writing, the boring bit, something that you might be picked up on or ridiculed for. And yet, as I have gone on with my writing, and my reading, I have become more and more interested in how and why plot works, and the different approaches taken by writers from Charles Dickens to Julian Barnes.

So the next seven posts will be a digest of Christopher Booker's seminal tome The Seven Basic Plots: why we tell stories. I hope you'll find this useful to read, and I'm sure I'll learn a lot myself.

But literary fiction is often more reliant on language, ideas and intellectual audacity than plot. I studied for my MA at Brunel, which favours solid plot construction. At UEA, still the creative writing equivalent of Oxbridge, plot is seen as somewhat middlebrow.

When I think about books I have read, what do I remember? Atmosphere, often, and character and scenes. In Bleak House, the brilliant opening and its depiction of foggy London. In Pride and Prejudice, the character of Lizzie Bennet with her razor wit and fine eyes. In The Girls of Slender Means, Selina Redwood squeezing through the tiny attic window with the Schiaparelli dress.

But I do remember plot. Both Affinity and Fingersmith turn on audacious and ingenious plot twists, and so does The Woman in Black. Sometimes plot can sneak up and change the whole meaning of a novel - English Passengers does this superbly and made me weep. Plots can be stunningly well executed - as in The People's Act of Love, or tragically simple, as in The End of the Affair.

I also suspect that, like me, many writers are intimidated by the idea of constructing plot. It always struck me as the Maths homework of fiction writing, the boring bit, something that you might be picked up on or ridiculed for. And yet, as I have gone on with my writing, and my reading, I have become more and more interested in how and why plot works, and the different approaches taken by writers from Charles Dickens to Julian Barnes.

So the next seven posts will be a digest of Christopher Booker's seminal tome The Seven Basic Plots: why we tell stories. I hope you'll find this useful to read, and I'm sure I'll learn a lot myself.

Sunday, 10 June 2012

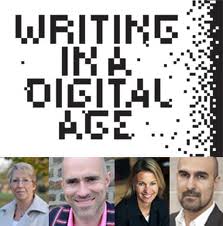

WRITING IN A DIGITAL AGE

Telling stories is a lot older than the paper book, and the effect of digital technology on this ancient art is going to be interesting. Not, as some commentators seem to suggest, terminal.

Yesterday I went to Writing in a Digital Age, a conference run by The Literary Consultancy and the Free Word Centre which highlighted some current trends. There was a good cross section of views: Robert Kroese, a self published US novelist whose Mercury Rises novels have been picked up by Amazon; a panel of international writers and poets chaired by Ellah Allfrey, deputy editor of Granta, and (the highlight for me) a smorgasbord of agents and editors given seven minutes each to summarize their approach and pitch their views.

The agent/editor slot was a piece of inspired programming. Each contributor was the prisoner of their own slide-show, required to keep pace with the changing images. They revealed more of themselves and their true passions than any group of publishing professionals than I have ever seen before (and I am a veteran of these gigs) and it was great to see/be reassured that traditional publishing may be undergoing seismic change, but still has much to offer both the would-be writer and battle-weary mid-listers like me.

While the conference raised more questions than it answered, it was a fascinating and surprisingly inspiring day. I suppose this surprised me because my suspicion is that digital might be unicode for 'tekkie faddism' in which originality is overlooked in favour of formulaic and genre-throttled dead cert fiction. (Which usually ends up being just as much a hostage to fortune as any other kind.)

But the message, coming loud and clear from all concerned, was that digital writing may offer new platforms for fiction and new routes to readers, but it is not a quick fix in literary terms.

Just to be completely old school for a moment, Thomas Carlyle described genius as 'a capacity to take infinite pains' and anyone thinking of self-publishing in the e-universe would do well to have this maxim pinned over their desk. Turgid narratives, editorial inaccuracies and Awful Covers are all marks of the hopeless amateur.

And the words come first - and last. As Kroese pointed out, digital success is no more accidental than success in traditional publishing. You need to work for it - and you need to spend time not just writing the best possible book, but presenting it in the most professional possible way.

Yesterday I went to Writing in a Digital Age, a conference run by The Literary Consultancy and the Free Word Centre which highlighted some current trends. There was a good cross section of views: Robert Kroese, a self published US novelist whose Mercury Rises novels have been picked up by Amazon; a panel of international writers and poets chaired by Ellah Allfrey, deputy editor of Granta, and (the highlight for me) a smorgasbord of agents and editors given seven minutes each to summarize their approach and pitch their views.

The agent/editor slot was a piece of inspired programming. Each contributor was the prisoner of their own slide-show, required to keep pace with the changing images. They revealed more of themselves and their true passions than any group of publishing professionals than I have ever seen before (and I am a veteran of these gigs) and it was great to see/be reassured that traditional publishing may be undergoing seismic change, but still has much to offer both the would-be writer and battle-weary mid-listers like me.

While the conference raised more questions than it answered, it was a fascinating and surprisingly inspiring day. I suppose this surprised me because my suspicion is that digital might be unicode for 'tekkie faddism' in which originality is overlooked in favour of formulaic and genre-throttled dead cert fiction. (Which usually ends up being just as much a hostage to fortune as any other kind.)

But the message, coming loud and clear from all concerned, was that digital writing may offer new platforms for fiction and new routes to readers, but it is not a quick fix in literary terms.

Just to be completely old school for a moment, Thomas Carlyle described genius as 'a capacity to take infinite pains' and anyone thinking of self-publishing in the e-universe would do well to have this maxim pinned over their desk. Turgid narratives, editorial inaccuracies and Awful Covers are all marks of the hopeless amateur.

And the words come first - and last. As Kroese pointed out, digital success is no more accidental than success in traditional publishing. You need to work for it - and you need to spend time not just writing the best possible book, but presenting it in the most professional possible way.

Monday, 28 May 2012

THE MOTHER OF INVENTION

So it's Monday, and I spent the weekend looking at my daughter's art show at her sixth form college, eating Turkish food in Stoke Newington and writing my PhD thesis with the blinds down because it was sunny. (Normal people were outside.) Also watched Dark Water* which was brilliant (slightly too scary for me, but I have to butch up now due to having teenage kids who aren't scared of anything). And I read some of Susanna Jones's new novel When Nights were Cold which is also brilliant and increasingly intense. Oh, and I did three loads of washing, went to two cafes and two pubs, walked round Clissold Park and spent 45 minutes at the gym.

But the writing? What about the writing? I was going to do one of those posts where I say, it's fine not to write for two days, because sometimes life closes in, when I remembered that last night I edited two short stories down to flash fiction length, and then had an idea for another story which I will write today. Writing can be done in corners of time, there is no need to rent a cottage on a Welsh mountain though I would dearly like to. (I wrote my first novel when I was a busy freelance journalist by pretending it was a succession of feature articles.)

Creativity doesn't need vast swathes of time. In fact, deadlines can be a useful prompt: check out Jonah Lehrer's book How Creativity Works if you don't believe me. Necessity really is the mother of invention. It's the deadline for the Bridport prize on May 31st, which is this Thursday. And that is all the prompt that anyone should need...

* N.B. Pedant's note: this was the Japanese version. Haven't seen the US remake, but as a general rule I'd rather see the original than the Hollywood imitation, subtitles or no subtitles.

But the writing? What about the writing? I was going to do one of those posts where I say, it's fine not to write for two days, because sometimes life closes in, when I remembered that last night I edited two short stories down to flash fiction length, and then had an idea for another story which I will write today. Writing can be done in corners of time, there is no need to rent a cottage on a Welsh mountain though I would dearly like to. (I wrote my first novel when I was a busy freelance journalist by pretending it was a succession of feature articles.)

Creativity doesn't need vast swathes of time. In fact, deadlines can be a useful prompt: check out Jonah Lehrer's book How Creativity Works if you don't believe me. Necessity really is the mother of invention. It's the deadline for the Bridport prize on May 31st, which is this Thursday. And that is all the prompt that anyone should need...

* N.B. Pedant's note: this was the Japanese version. Haven't seen the US remake, but as a general rule I'd rather see the original than the Hollywood imitation, subtitles or no subtitles.

Friday, 25 May 2012

DRAFTING

After the notebook - drafting. A notebook is the writer's dumping ground for random thoughts and scribbles, and the first draft marks the next stage in the creative process. These days some writers - maybe most - write their first draft on a PC or laptop. But there are others, including Patrick Gale, who stick to the traditional pen and paper method when developing their early ideas.

What seems sad to me is that with fewer writers using the old school approach, there will be fewer chances to see a first draft in all its muddled glory. (Track changes just aren't the same.) Shakespeare may never have blotted a line but most writers blot and scratch out at will, and a first draft is fascinating to read.

Case study. Charles Dickens. Here is the first page of A Tale of Two Cities...

What seems sad to me is that with fewer writers using the old school approach, there will be fewer chances to see a first draft in all its muddled glory. (Track changes just aren't the same.) Shakespeare may never have blotted a line but most writers blot and scratch out at will, and a first draft is fascinating to read.

Case study. Charles Dickens. Here is the first page of A Tale of Two Cities...

I love this - it's like watching him thinking. Of course, had Dickens had access to a laptop, he would probably have written about 97 more novels. (Though there are those who think he would have been writing soaps or screenplays, who knows?) But in any case, there it is. He didn't, and we are the richer for it.

The Victoria and Albert Museum has Dickens' whole manuscript for A Tale of Two Cities up on its website. And you can also access it through the Penguin English Library.

Sunday, 20 May 2012

A PUNCH UP THE PAVILION

I'm going to blog soon about reading aloud and current vogue for literary 'slamming' and 'gritting' and so on: i.e. the newly sexy live authorial reading with the lights down and the stories short.

Not all writers want to stand up and read in front of a paying audience, and not all readers want to go to live events. And there is no way that any writer, no matter how ebullient, extrovert and vocally gifted, can rival live music or actual drama, in my humble opinion. But sometimes this is the best/only way of reaching your potential readership.

It's four years since I read this piece at the Brighton Festival and it marked a turning point in my writing. I realised that I could 'do' short, and that people liked it. And I realised that there is humour in even the worst things that can happen to you. In this case, being punched by a stranger at my own wedding.

So here it is - A Punch Up the Pavilion.

Our invitations say: “We’ve had the booze, the fights, the kids and the cardigans.

Now it’s time for the wedding.”

The Pavilion is

the venue. The red drawing room. Hence

the frock – floor length scarlet. strapless satin, with a bit of a train. The

black taffeta shrug doesn’t quite fit,

it’s a teeny bit tight. My shoulders

have a faintly gladiatorial look. I had the whole ensemble made - for the grand

sum of sixty quid - by a retired midwife with face piercings. So we’re not

talking Liz Hurley levels of outlay here.

I’m wondering if

it’s all a bit too Goth?

My mother

envisaged me in raw silk separates, cloche hat, cream roses: Gatsby garden

party styled by Next. Since I passed the

40 mark, she’d rather I were swathed in neutral shades, as if I was an object

of minor interest in a National Trust property, in need of protection from out-of-season

dust.

My friend

Bernadette – a serial divorcee, and an expert in bridal dos and don’ts – told

me to “hold the moment” at some point during my big day. “You must take a step

back, and think – this is it,” she said. “It is your one and only wedding day. A once-in-a-lifetime

experience.” Bernadette has had a once-in-a-lifetime experience three times, so

she knows what she is talking about.

This is it,

then.

I’m standing on

the windy lawn at the back of the Pavilion. The weirdly corporate little

ceremony is over. We’ve processed out of the drawing room with Ella Fitzgerald

in the background. The children are leaping around me, my son in his grown-up grey

suit, hands in his pockets like a boy in an old photograph, my daughter in her

wreath of pink lilies, gold hair down to her shoulders. My legal “husband” is

corralled by the Irish relatives, not able to think of much to say to them.

Everyone is smiling, smiling. There are

blank spaces between the groups of ill-assorted guests.

A swift breeze whips

my hair across my eyes so I am blinded for a moment and I don’t see her coming.

And then she is

there, standing right in front of me. Addled by bridal celebrity, my brain just

gets an image, no information attached.

A woman with a set face, white and undernourished. Her thin hair is

stretched tight against her skull, as if she hates it and has strained it back

for a punishment. She is small-eyed and zipped into a light blue padded

jacket.

We look at each

other.

“Are you the

bride?” she asks.

“Yes, “I say, flushed

and grinning. “I am.”

Then, there is a

black thud, obscuring everything. My head goes down, my hands go up to clutch

my face. My bouquet of oriental lilies

falls, and no one catches it. A scream from my daughter. There is a dull, hard

pain. Gasping, I open my eyes, and there’s the world at ground level. Gobbets

of chewing gum and sun shrivelled grass.

The woman is standing quite still. I can see her jeans and her smart new training

shoes, complete with price tag. Pale blue to go with the jacket.

“She’s punched

her!” shouts somebody. “Arrest that

woman! She punched the bride!”

I look up. The guests

are now united, surging towards us. The woman turns and legs it, hurtling

across the grass, powering herself forwards with her arms. My mother tries to

chase after her, her angry feathery headgear fluttering in the wind. My mother is restrained. Other guests give

chase as well, but the woman is faster. She leaps the wall by the bus stop, and

disappears. I feel completely alone, cut

off in my sudden little violent space.

Then I remember Bernadette. “Hold the

moment”. Hold the buggering moment. Not

much point in that now. I straighten up and look at my hands. No blood. No

damage done. My nose feels twice its natural size, but is still there. I look

around me, at all the anxious faces. Everything ruined.On my once-in-a-life-time

wedding day.

At the Arts Club, bottles of chilled cava are lined up on the bar,

ready to toast our journey into married old age. Later, there will be a salsa band and sixteen

kinds of salad.

“Come on everyone,” I say, hitching up my skirt so no one treads on

my mini-train. “I need a drink.”

And off we go, tripping along through the

Laines , an ungainly crocodile of wedding folk: me, husband, sobbing children, Irish relatives

and incompatible guests. Then we dance all afternoon and most of the night.

* * * *

Afterwards, I

found I wasn’t the only one. There were other brides, other punchees. She used

to go to the drop-in centre for street drinkers next door to the Pavilion.

She’d been unlucky in love, as in most other areas of life.

Brides seemed an obvious target, smugly ponced up in their

cream-cake crinolines. Over privileged and easy to identify. I sort of saw where she was coming from.

I wear a thick gold ring now, like a knuckle duster. And I wonder what she did next? If she moved on from punching brides and

settled for something safer. Or if, her trainers still that pristine shade of

arctic blue, she kept on running.

Tuesday, 8 May 2012

THE ART OF SEEING

While I was walking round the Lucian Freud exhibition on Saturday evening, I wrote this down on an old envelope (having left my notebook at home, bad girl): 'Why are art galleries so tiring? It's as if our eyes are muscles that we rarely use.'

Weird idea, because of course everyone who can see must be looking at things all the time. But we can 'look' without seeing, on the autopilot that Virginia Woolf calls 'non-being'. What I find inspiring about Lucian Freud, love him or hate him, is the intensity of his seeing, and the way he makes the human form loom up at you, more vivid and realised than the actual people looking at the paintings on the wall.

I don't find his work offensive, but affirming. The fact that most of his models are not conventionally beautiful is inspiring in itself. The (literally) cocky Leigh Bowery, bald head set magisterially on his bulbous torso; the artist's mother with her withered, fragile hands; Big Sue the benefits supervisor (above) spilling over a sofa like a pile of plump flesh cushions: these all made me realise that I spend a great deal of my life hating my own body, apologising for it, promising that it will be narrower, firmer, more controlled, in future. But it's really all I am, all I've got.

Really seeing, as well as looking, is a homage in itself. It doesn't matter if you depict your subject sympathetically or - as Freud does - forensically. This picture of his children, crowded together and yet all separate from one another, looks to me like a celebration of the strangeness of family life, and the ruthless self-absorption of childhood and adolescence.

How does this relate to writing? Ah, well. That's for anyone who wants to write to work out for themselves...

Weird idea, because of course everyone who can see must be looking at things all the time. But we can 'look' without seeing, on the autopilot that Virginia Woolf calls 'non-being'. What I find inspiring about Lucian Freud, love him or hate him, is the intensity of his seeing, and the way he makes the human form loom up at you, more vivid and realised than the actual people looking at the paintings on the wall.

I don't find his work offensive, but affirming. The fact that most of his models are not conventionally beautiful is inspiring in itself. The (literally) cocky Leigh Bowery, bald head set magisterially on his bulbous torso; the artist's mother with her withered, fragile hands; Big Sue the benefits supervisor (above) spilling over a sofa like a pile of plump flesh cushions: these all made me realise that I spend a great deal of my life hating my own body, apologising for it, promising that it will be narrower, firmer, more controlled, in future. But it's really all I am, all I've got.

Really seeing, as well as looking, is a homage in itself. It doesn't matter if you depict your subject sympathetically or - as Freud does - forensically. This picture of his children, crowded together and yet all separate from one another, looks to me like a celebration of the strangeness of family life, and the ruthless self-absorption of childhood and adolescence.

How does this relate to writing? Ah, well. That's for anyone who wants to write to work out for themselves...

Writing what you know

'Write what you know' the saying goes. So (notebooks bulging with ideas) off we go with our stories about obsessive first love or scarily weird parents. If your break-ups have been amicable, and your family is functional, you are at a disadvantage.

But if I were to be all academic about it, I might say: how do you define 'know'. Do you mean 'remember'? How do you know your memories are accurate? Do you mean 'feel'? What vocabulary do you have to communicate your emotion to someone else, so they can feel it too?

In an excellent book about writing called 'The Agony and the Ego', Graham Swift suggests that that we should also write about what we don't know. You can learn to 'see' the material for your writing.

Research is as important to good writing as vividly recalled experience, and the skill of noticing, and using words with unselfconscious skill. Good writing comes from a sort of meticulous honesty.

A.L. Alvarez says writers need two things:

* 'The particular faculty of mind to see things as they really are, and apart from the conventional way in which you have been trained to see them.'

* 'The concentrated state of mind, the grip over oneself which is necessary in the actual expression of what one sees'.

More on 'seeing' soon, courtesy of the genius of Lucian Freud...

But if I were to be all academic about it, I might say: how do you define 'know'. Do you mean 'remember'? How do you know your memories are accurate? Do you mean 'feel'? What vocabulary do you have to communicate your emotion to someone else, so they can feel it too?

In an excellent book about writing called 'The Agony and the Ego', Graham Swift suggests that that we should also write about what we don't know. You can learn to 'see' the material for your writing.

Research is as important to good writing as vividly recalled experience, and the skill of noticing, and using words with unselfconscious skill. Good writing comes from a sort of meticulous honesty.

A.L. Alvarez says writers need two things:

* 'The particular faculty of mind to see things as they really are, and apart from the conventional way in which you have been trained to see them.'

* 'The concentrated state of mind, the grip over oneself which is necessary in the actual expression of what one sees'.

More on 'seeing' soon, courtesy of the genius of Lucian Freud...

Thursday, 26 April 2012

The Notebook

I have several note books on the go at any one time, which is not necessarily a good thing. There's a sort of panicky moment when I wonder which one should get the Great Thought, or the note about buying eggs. There's a small one in my bag, which currently has morphed into a slightly big one because my daughter gave it to me, and it has a fancy cover. Then a medium sized moleskin one in my briefcase, which is quite serious looking and I like to get it out for my supervisions in case it makes me look intellectual.

And then a massive, ring bindery one that lives on or near my desk, and is meant to be the repository of ideas for the New Novel. (Not much going on in that one at the moment due to the fact I am still wrestling my thesis to the ground, and it's proving a rather tricksy little blighter.)

But are notebooks really necessary? Is writing in your little book the only way of communing with your undeveloped ideas? Bruce Chatwin made quite the fetish out of it, but other writers seem to get on fine with lap tops or the backs of envelopes. One friend of mind carries a Dictaphone round with her, and of course fashionable people use their iPhones.

I still like the scribbling thing, myself. Keyboards are quick and efficient, but there is something very natural and simple about sitting there, thinking, pen in hand. Keyboards drive you on, eyes gripped by the electric emptiness.

And of course a notebook is also a way of breaking away from that white screen, and thank God for that. And notes are tactile, you can do little drawings, or underlinings, or scribble out the rubbish with a great flourish. The delete button isn't half so satisfying.

And then a massive, ring bindery one that lives on or near my desk, and is meant to be the repository of ideas for the New Novel. (Not much going on in that one at the moment due to the fact I am still wrestling my thesis to the ground, and it's proving a rather tricksy little blighter.)

But are notebooks really necessary? Is writing in your little book the only way of communing with your undeveloped ideas? Bruce Chatwin made quite the fetish out of it, but other writers seem to get on fine with lap tops or the backs of envelopes. One friend of mind carries a Dictaphone round with her, and of course fashionable people use their iPhones.

I still like the scribbling thing, myself. Keyboards are quick and efficient, but there is something very natural and simple about sitting there, thinking, pen in hand. Keyboards drive you on, eyes gripped by the electric emptiness.

And of course a notebook is also a way of breaking away from that white screen, and thank God for that. And notes are tactile, you can do little drawings, or underlinings, or scribble out the rubbish with a great flourish. The delete button isn't half so satisfying.

Monday, 23 April 2012

SCHLOCK HORROR!

Soon, very soon, I will be posting some very impressive stuff about The Authorial Journal and quoting Plato and other eminent ancients about the finer points of writing. But as it's a wet Monday, and I am so tired I put my son's birthday cake in the oven with no margerine in it, I am going stick to something a tad more downmarket.

So here it is. I went to see a film with him in a pre-birthday spirit of doing whatever a 15 year old wants to do, and what he wanted to was go to a Chinese buffet called Max Orient in Camden and from thence to the Odeon Parkway to see this...

And, considering I spent about one third of the movie under my jacket, as I do not do schlock, I really liked it. It's a clever, genre busting, imaginative story, not in the least witless. And a reminder that it is a good idea to get well outside your comfort zone - quite literally in this instance - if you are interested in story telling. Surprise, inventiveness, cracking dialogue and Sigourney Weaver - if I can produce stories that are the literary equivalent, I will be a happy woman.

Here is the trailer. Jacket at the ready...

So here it is. I went to see a film with him in a pre-birthday spirit of doing whatever a 15 year old wants to do, and what he wanted to was go to a Chinese buffet called Max Orient in Camden and from thence to the Odeon Parkway to see this...

And, considering I spent about one third of the movie under my jacket, as I do not do schlock, I really liked it. It's a clever, genre busting, imaginative story, not in the least witless. And a reminder that it is a good idea to get well outside your comfort zone - quite literally in this instance - if you are interested in story telling. Surprise, inventiveness, cracking dialogue and Sigourney Weaver - if I can produce stories that are the literary equivalent, I will be a happy woman.

Here is the trailer. Jacket at the ready...

Sunday, 15 April 2012

Right here, right now

Oh, the trials and tribulations of the Literary Career! You are either banging your head on the keyboard, fretting about Writers More Successful Than You Are, scrutinizing Amazon to see if your Oeuvre has risen above the half-millionth mark or worrying about all known subjects, including the Eurozone, global warming and the safety regime at the Grand National. (Or is that just me? I can't stand seeing photographs of the falling horses, all those heavy bodies crashing down as they leap over Becher's Brook.)